Descriptive language is a great persuader, as I wrote in my most recent ‘column’ (what do you call a piece of writing which has no presence on paper?) in Building Design. Elizabeth Hopkirk’s spirited defence of No 1, Poultry as a contender for the best building of the century at the 20th Century Society event held at the Royal Academy recently was a case in point. Neither she nor I, arguing for the deteriorating Shredded Wheat silos in Welwyn Garden City, achieved enough marbles (the means of voting) to make the final shortlist – which suitably enough opted for social and communal values over aesthetics and history – but her presentation galvanised the audience, many of whom I suspect might not have given the major Post-Modern building in the City (from 1997) more than a glance or even sneer until now.

But verbally spot-lit, Stirling’s late London building (Peter Palumbo’s replacement for the posthumous Mies van de Rohe tower proposed), immediately sprang into high relief. I am still taking my time to readjust to PoMo (a problem of my generation, blinded by its bland excesses, perhaps?) but my estimation of No.1 Poultry rose by leaps and bounds. In her defence of the building, Elizabeth Hopkirk pointed to the colourful interior windows around the central core court and suggested that they seem to invite washing lines strung between them. When she found herself sitting outside the Royal Exchange eating sandwiches in the sunshine, the stepped complexity of the building form as it cornered and rose above its site intrigued and pleased her. It all demonstrated to me how stale our (well, my) own viewpoint can become, and how essential is the nudge, or something more forcible, towards adjusting it, changing our approach, giving pause for thought and consideration of a different point of view. Language and figures of speech carried the argument.

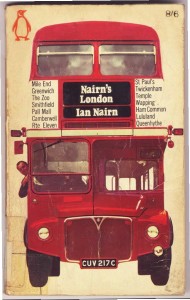

Ian Nairn knew how to employ those. Fifty aficionados spent a late November Sunday on the same Routemaster (CUV 217C) that graces the cover of Nairn’s London (1966) looking at a slice of east London and the City through his eyes. Let me remind you of how he wrote (and his book is now back in print, in a facsimile edition from Penguin). At random, an offbeat analogy to conjure up an unusual City church (of St Mary Aldermary ‘Wren treated Gothic as if it were a cantankerous old aunt: with affectionate disrespect’), a joke to introduce some Gothic Revival almshouses (Holly Village, Highgate, ’an endearing group of hedgehogs’), gearing up to describe a Brutalist tower block (Eros House Catford where ‘rough concrete is put through all its paces’) or simple praise for a modernist block of flats (Highpoint 1 ‘can still provide, a little diminished, the thrill of the thirties’). It is that ability to compress a notion of the technical or the historical within a telling phrase that made Nairn, on the page or on film, the master – in print his words carefully weighed and measured, on television off the cuff and straight from the heart.

I have been writing about the youthful John Summerson recently (see AA Files 69, due any day now) and once again was overwhelmed by his elegance of language, his incisive mind and intellectual hinterland. Nairn confessed to going through Summerson’s Georgian London with a ‘toothcomb’ when writing his own masterpiece.

The challenge set by Nairn remains. Jonathan Meades has torn up the rulebook and recently brought Brutalism, by some obscure back lanes and diversions, to the portion of the nation that catches BBC4. Meades’ language is thoughtful, exultant and menacing by turn, and frequently his choice of analogy intriguingly opaque, but it all serves to burn the accompanying images into brain and retina. That’s what strong words can do for good buildings – make them better.

@gilliandarley

@gilliandarley @gmdarley

@gmdarley Gillian Darley

Gillian Darley